Chimurenga Chronic

Mafika Gwala emerged as a significant writer in the 1970s during his association with the black South African Student Organisation and the Black Community Programmes in Durban. In 1973 he edited Black Review, and his short stories, essays and poems have been published in numerous journals and anthologies. His poetry collections include Jol’iinkomo (1977) and No More Lullabies (1982). He also worked with Liz Gunner and co-edited Musho! Zulu Popular Praises (1991), a literary commentary on Zulu poetry which includes two of his praise poems. A prominent activist and an advocate of Black Consciousness, his poetry rose out of poverty, oppression, physical and mental pain to reclaim dignity and beauty. Writing in the spirit and rhythm of jazz, he creates living music, finding the perfect low tone of oppression and the highs of liberation.

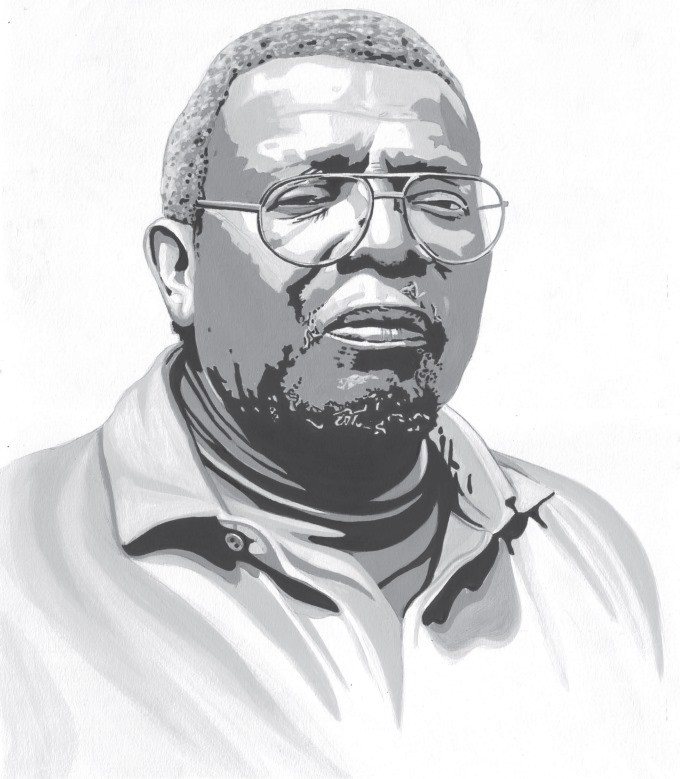

At age 68*, Gwala has lost none of his fire. He talks to fellow poet Lesego Rampolokeng about the ANC, black consciousness, Biko and liberation – then and now.

Lesego Rampolokeng: We don’t need to start with any false greetings, we are here, we are established, right? Let’s just get into the thing. I’d like to start with a few quotations from a piece of writing deeply relevant to me personally, to my existence, to my coming to consciousness, your piece “Getting Off The Ride”:

They say the black ghost is weak/That it is feeble and cannot go the distance/I say that’s their wishful thinking.

And I’ll jump to somewhere else:

Sharpeville’s black ghost haunts all races, urges the black people forward/I live with this ghost/I’ve come to love this ghost/I live with the black ghost.

And then elsewhere we get to definitions of blackness:

I ask again, what is black? Black is when you get off the ride/Black is point of self-realisation/Black is point of new reason/Black is point of no national deception/Black is point of determined stand/Black is point to be or not to be for blacks/Black is point of “right on”.

And you said elsewhere:

Black is energetic release from the shackles of “kaffir, “bantu”, “non-white”.

That has helped me define my place in this world. So I’d like us to start with this, by asking what your definition of black consciousness is? Why we need it and – if we do – why we need black consciousness in this time?

Mafika Gwala: Well, black consciousness is just a part of what we need in our societal attitudes. There are more things to consider than just blackness. Though black consciousness is a way of looking at yourself and putting minus to those things that we don’t need. But right now we need black consciousness, not the way black consciousness was. We need a better black consciousness because when we have people running to parliament on the black consciousness ticket, then you ask yourself, “What’s going on now?” Recently we have had a leader who was so much part of black consciousness going to the DA [Democratic Alliance]. Now there you question this black consciousness. As I said in 1971: black consciousness is not an end in itself. It’s a means towards an end. We needed black consciousness to correct the many errors that had been committed by our leadership.

LR: That’s beautifully put. I encountered in your writing not just engagement with our existence, it was not just about the content, although the content was paramount, it was pointed and powerful, revolutionary. Even the form itself was revolutionary. And while working within black consciousness or the black perspective it swung out internationally. It swung out to the people of Guinea Bissau, it swung out to the people of Vietnam, to the people of Cuba. What are the links between our struggles, our existence and those of those other people and why was there a need to put them in writing? Your poetry moves – let me put it in the present tense because it doesn’t die, it doesn’t really matter when it was published, it is alive and it will be, tomorrow and the day after – it moves from our specific reality right here at the southern tip of the African continent and it embraces the people of Guinea Bissau and it goes out of the people of …

MG: Vietnam…

LR: Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh. Beautiful, beautiful piece. I loved that you wrote, “And it goes to the people of Cuba”. What are the links or, should I say what was the original impulse towards writing to and about or for speaking to those people in the writing?

MG: Well, it started off by asking myself why is it that when we write we give the whites a chance to manoeuvre us? In other words, why address white South Africans instead of addressing ourselves amongst ourselves, through the struggle, asking how it should go and what is happening and what has been a failure? So we had definite goals within black consciousness. But then we started losing them one by one, dropping them off, dropping them off. The more dashikis we had, the more bourgeois we got. Then Vietnam, Vietnam was an essential part of our struggle. Because from there we could learn something like black consciousness should not be around colour. It should be around the natural struggle of people wanting identity themselves as a whole. Same with the Cubans. The Cubans taught us that we had to stand on our own because we wouldn’t liberate ourselves if we always thought that some people were doing it for us. And it even came to Cuito Cuanavale. Cuito Cuanavale taught us that now was the dead-end street. There was no going further. It meant open confrontation with the system, against the system.

The people of Guinea Bissau, they taught us lots of things. They taught us tolerance. They were divided, a diverse society actually. But within that society they sought unity and they readily found it because they were honest with their principles. Unlike what’s going on with us. It seems to me we have lost the revolution – but not completely, we can still make amends. We think we have made it with freedom, but where is the liberation? It seems our revolution, our democratic revolution, national democratic revolution, has been betrayed or suspended. We still think that owning a BMW and Mercedes Benz is not in conflict with our national quest for greater freedom. We think we have made it, when we actually haven’t made it. Already we are diving for the negative side of it. Look at what happens now. I am sorry I have to repeat this. Look at what happens when a person who was deeply involved in black consciousness moves over to the DA. It shows that Vietnam was right. The struggle is class-based. It’s not colour-based. It’s not that I’m a Vietnamese, I’m fighting Vietnamese against America. It wasn’t just that. It was what do you stand for as an individual, to show that you want liberation for Vietnam? We seem to have forgotten that. So that now what happens is we make lots of noises about liberation, about tolerance, when we know very well in our hearts that what tolerance means for some people is tolerating the corruption that has started to emerge. It can still be stopped. There is still a chance for it to be stopped.

LR: Taking it from what you’ve just said, explained very beautifully… is there a concerted effort, should one say, or is there an agenda that seems to be in place, to present our problems as not being class-based within South Africa, right now? Because we keep hearing, watching TV, reading the news, that progress is being made, that there’s gross alleviation of poverty, that there are more houses being built; we get bombarded with those images every single day.

MG: I think we are being used as vehicles for a welfare state, away from the revolutionary thread that was taken by many organisations in this country. It seems that class struggle is being dodged. But we can’t get away with it. Some people were given a better deal because of the situation surrounding us. And the question is: those who didn’t get the better deal, how long will they continue tolerating the system for the sake of tolerating our identity as a South African nation?

LR: Would one be right then to say that revolution is imminent? That, if things continue as they do, there is bound to be a total overhaul, an organic one, one that springs from within the people themselves? I ask this because we spoke to a poet – I won’t mention the name I guess because I don’t think we need to be attacking him personally – from the SACP who is in parliament and he was giving us really governmental talk, about: “We know we’ve got problems, but we’re working on them.” We approached him as a poet and it seems to me that there is a need for the poet to die in order for the politician to rise in those circumstances. That’s what came to me anyway. That leads me to you. There were, I wouldn’t say opportunities, but there was a chance for you to be in parliament. Why did you not go into parliament?

MG: Ja, being in parliament is not a priority for any person who thinks in terms of revolutionary situations. Being in parliament is just… a sideways jump. We don’t need parliament for us to think that we need a better society – better than what is being given to the people now. And yet there is so much of corruption going on in the name of struggle, in the name of democracy. We have to go back to ourselves, our old selves under the regime of the nationalist government and say we want freedom, not freedom with a compromise as it has happened. Because this question of alliances, alliances, Congress Alliances, if you realise it deeper, there is a lot of cheating going on. People are saying, “If you are not part of the Democratic Alliance…”, not Democratic Alliance, Congress Alliance. I’m sorry, Congress Alliance, not Democratic Alliance (laughs). I’m giving Helen Zille big clout. The Congress Alliance should go on, but not as it is going on now. Because if you are talkative on issues – like the poet you spoke to, we don’t mention his name – they silence you. They give you a position in government and you are silenced. Blade Nzimande is silenced. He is no longer the Blade we knew: the militant, devil-may-care character he used to be.

LR: Taking that into the literary sphere, is there a need right now for the poetry of insurrection, the poetry of revolution? I would not say “protest” because we’ve kicked that in the teeth and left it for dead. Things that people like Stephen Watson used to say about how there is no black poet in this country, you know the custodians of the English tradition, the British – to be specific – tradition, who are trying to pull down your writing and the writing of other people who were coming out, using the word as a vehicle, as a tool and a weapon to push us forward. Is there a need for the poetry of insurrection at this point, in this moment?

MG: There is need, but there also can be no need. It is a dualist kind of thing. On one hand we shouldn’t worry our present government too much because they have a heavy job to do. On the other hand we shouldn’t be complacent and pretend nothing wrong is happening when we can see that there is a lot of wrong going on. So we are also like trapped, we don’t know which way to go. So there is need for revolutionary poetry. But then when it becomes revolutionary, it’s condemning the very people who say they have liberated us. When actually we haven’t been liberated, we’ve just been granted freedom.

LR: Beautiful, beautiful. Do you see any need for black consciousness philosophy in the current South Africa? Is it still relevant? Precisely because today there are people who really have taken that and run with it. Whatever people, there are people today, that black boy – again we don’t have to mention his name, we can just call him Black Boy. Again there are people who define themselves as Bikoists, whose core target is whiteness. And they have reduced black consciousness almost to a slogan that whiteness must die.

MG: There’s no need for us to think that whiteness must die. Ideas or ideology of whites being superior that must die. But whiteness per se, there’s nothing wrong with whiteness. Biko himself made mistakes. He wasn’t a revolutionary in the first place. When he had to choose between Azapo and the Congress Alliance or PAC, he chose Azapo, which shows he wasn’t a revolutionary. He didn’t identify himself with the huge masses of people fighting the struggle in this country. He thought that the BC elite, black consciousness-wise, was the ideal that the nation had to take on. But it wasn’t. Biko himself made mistakes. When we said that black consciousness has bourgeois overtones, just like negritude, which Frantz Fanon explained so clearly when he talks of national consciousness and he identifies the revolutionary idea: “away from negritude as negritude”.

So we have to give due regard to people like Biko. If there are now in Joburg people, as you say, who are Bikoists, they don’t know what they are talking about because already Mamphele has gone to the Democratic Alliance. Where is Biko then? Plus, there is no Biko without bourgeois background. He aspired to bourgeois rights. That’s why we didn’t agree with him. As a writer, as a poet, categorically, I agreed with him, I admired him, we got along very well. But when it came to politics he would readily say, “The trouble with you is that you are a Stalinist.” He would call me a Stalinist. We were friends, we used to drink together. He enjoyed beer, I enjoyed beer (laughs). So he would say, you know, the trouble with you is that you’re a Stalinist. But there was nothing Stalinist about it. It was just that he was not seeing the revolutionary path.

LR: People don’t say this because what they’ve reduced him to is a raconteur, a face on a T-shirt, on a poster. They don’t dig beyond the superficial image that gets thrown at us. My core question then would be: this is 2014, in 1994 we had the first democratic elections and people are getting into a celebratory mood. We’re told we should be celebrating, we should be grateful, we’ve travelled this path. Like Fanon said, “Look how far we have come in this time.” Is there cause for celebration? Should we be celebrating? If one were to gauge it, how much? Or how much of this celebratory mood is misguided?

MG: I agree with the last statement. The celebratory mood should not be discarded because people have expectations. People want to know what Zuma is doing for them. People want to know what Blade Nzimande is doing for them. So that cannot be discarded. On the other hand there is nothing to celebrate. The revolution is still very young.

LR: Then I am going to ask you, my brother, to address, based or not based on these questions, just anything whatsoever about our current state and the way we should be pursuing, the path we should be going down from now into the future, anything whatsoever. What mistakes we seem to be making as writers, as activists, as just people walking up and down the street in this time. I ask you to just tell us.

MG: Number one: we should remain loyal to the African National Congress because it’s got a long history full of mistakes, full of hopes, full of successes. So we should respect that. Meanwhile when things are going wrong we shouldn’t keep quiet, pretend that nothing is going wrong. This is what seems to be happening now. People pretend that there is nothing going wrong. Once you say something then you’re anti-ANC. Then you are a sellout. Then you are a Bikoist. It’s taking us nowhere. That kind of attitude is not taking us anywhere.

Next door to me is the garage and that garage is sometimes teeming with youth. They don’t know what’s going on now. And they don’t hide that. They tell you: “We are young, we don’t know what you people did for us. But what we think you should be doing for us, that’s more necessary for us to think about now.” So it’s like that they are blackmailing us, but they are not actually blackmailing us. They just want direction. They argue a lot. I meet them there in this garage next door and we argue, we argue. But they are not wrong. We are pushing them to register for voting. They agree, one points at another, he says, “So-and-so hasn’t yet registered.” And I say, “So-and-so, why is it that you haven’t yet registered for the voting in time to come so near now?” Then he says, “No, it’s just that I am not clear about what we want to achieve.” How can you say I am not clear about what we want to achieve? You should be asking questions if there is something that you want to know. “No, it’s just because I’m shy to talk. I’m shy.” Just like that. These youngsters. They are promising, but haai, it’s a hell of a job, to put them in the right direction.

LR: I wonder if it’s not because the landscape (the social, the political) got rather murky, with the advent of the new dispensation. And so that confusion, within not just the youth, but the South African people in general. I’m talking about, for instance, what is referred to as xenophobic attacks, when it is essentially attacks upon and assaults upon the darker hue who are deemed to be from beyond these imperialist-defined borders of ours. I wonder if that has got a lot to do with the misdirection that came in, of course, with this ushering in of this new age, this new day that came with 1994?

MG: Yes, the young people are not far away from the tree, as fruit they haven’t fallen very far away from the tree. They are very close to the mainstream of the struggle. All they need is just being pushed a bit into the shade of the tree. Into the shade of the tree, so that they don’t suffer the African sun.

LR: Oh, ubaba, would you like to read some poetry for us?

MG: Should I start?

Thank you Mafika Pascal Gwala, 5 October 1946 – 3 September 2014.